Rethinking LLM Interfaces: AI powered data curation for Pharmacological Research

The real barrier to LLM adoption in pharma

Large language models can extract and structure data from clinical literature in minutes. Tasks that once took teams of researchers days or weeks can now be done almost instantly. For pharmaceutical companies running model based meta analyses, this is a genuine step change. The technology works. The models are capable.

The problem is not accuracy or performance. The problem is usability.

Clinical researchers often struggle to use these systems effectively because good prompting demands domain knowledge that lives in their heads, not on the page. To get the right data out, you need to specify drug names, targets, dosing regimens, patient populations, outcomes, and study designs with real precision. Asking a researcher to write that prompt from scratch is a bit like asking them to write a SQL query. They know what they want, but not the language needed to express it.

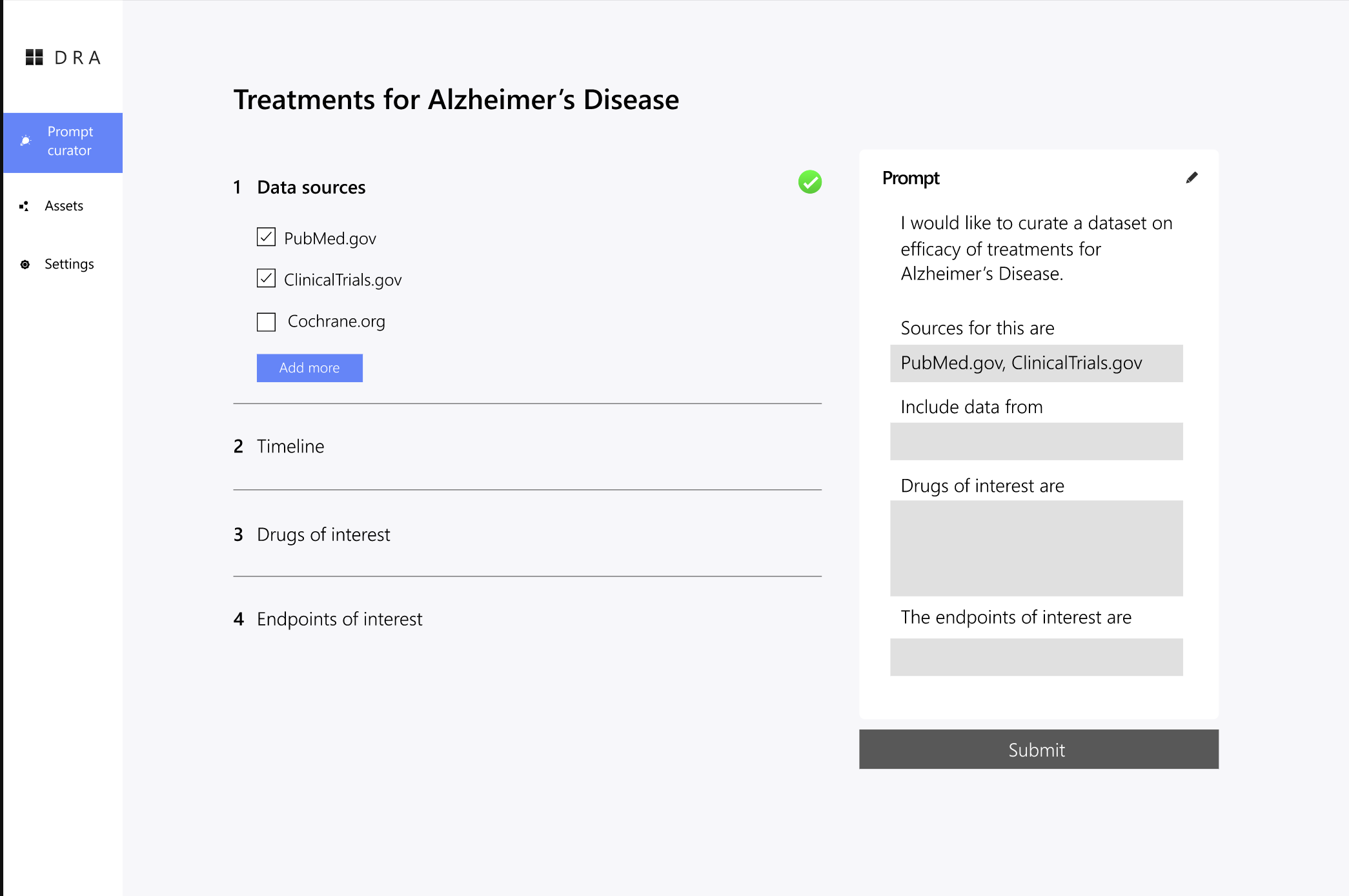

This project explored a different approach. Instead of turning researchers into prompt engineers, we asked how an interface might help them think through the problem step by step and arrive at the right prompt naturally.

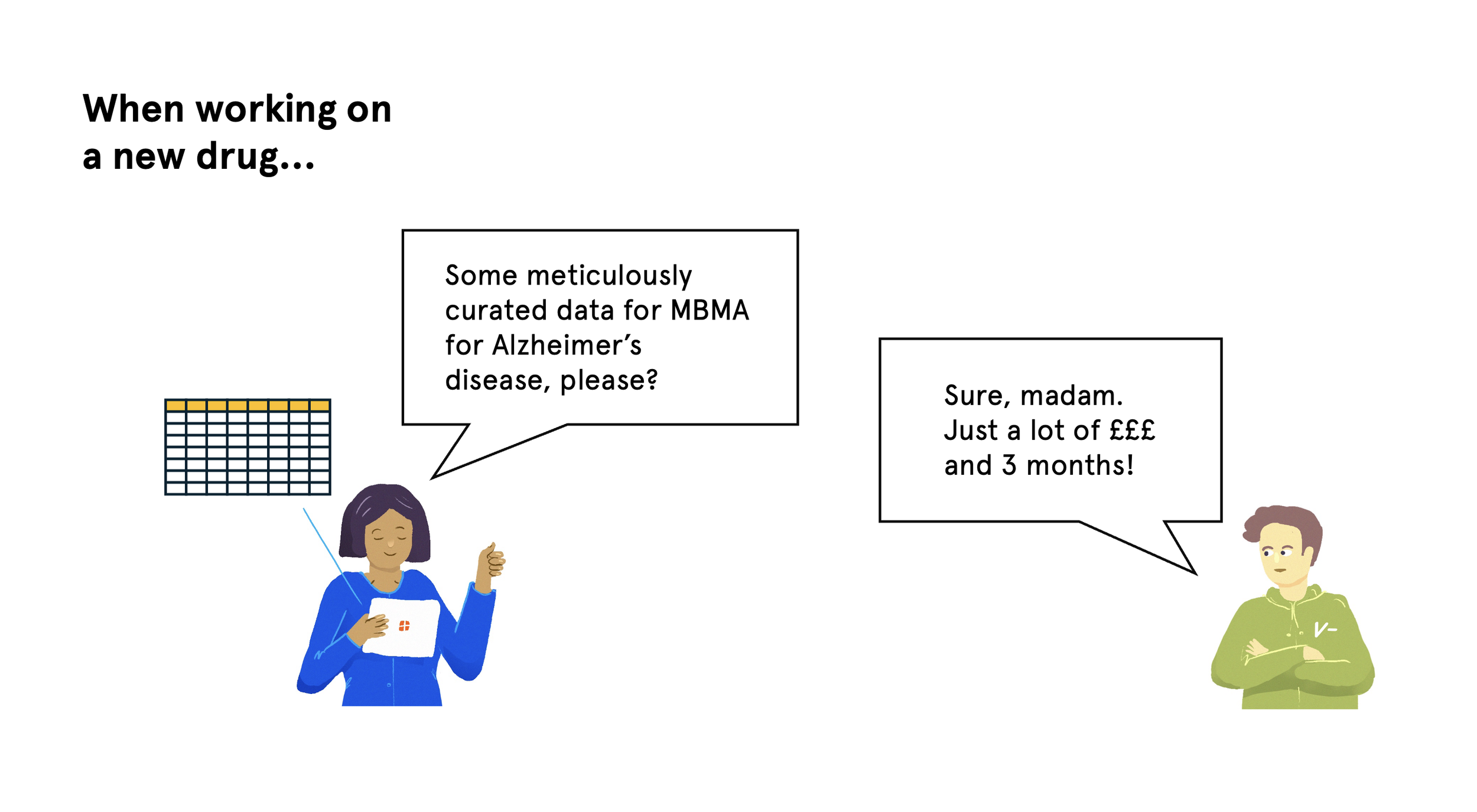

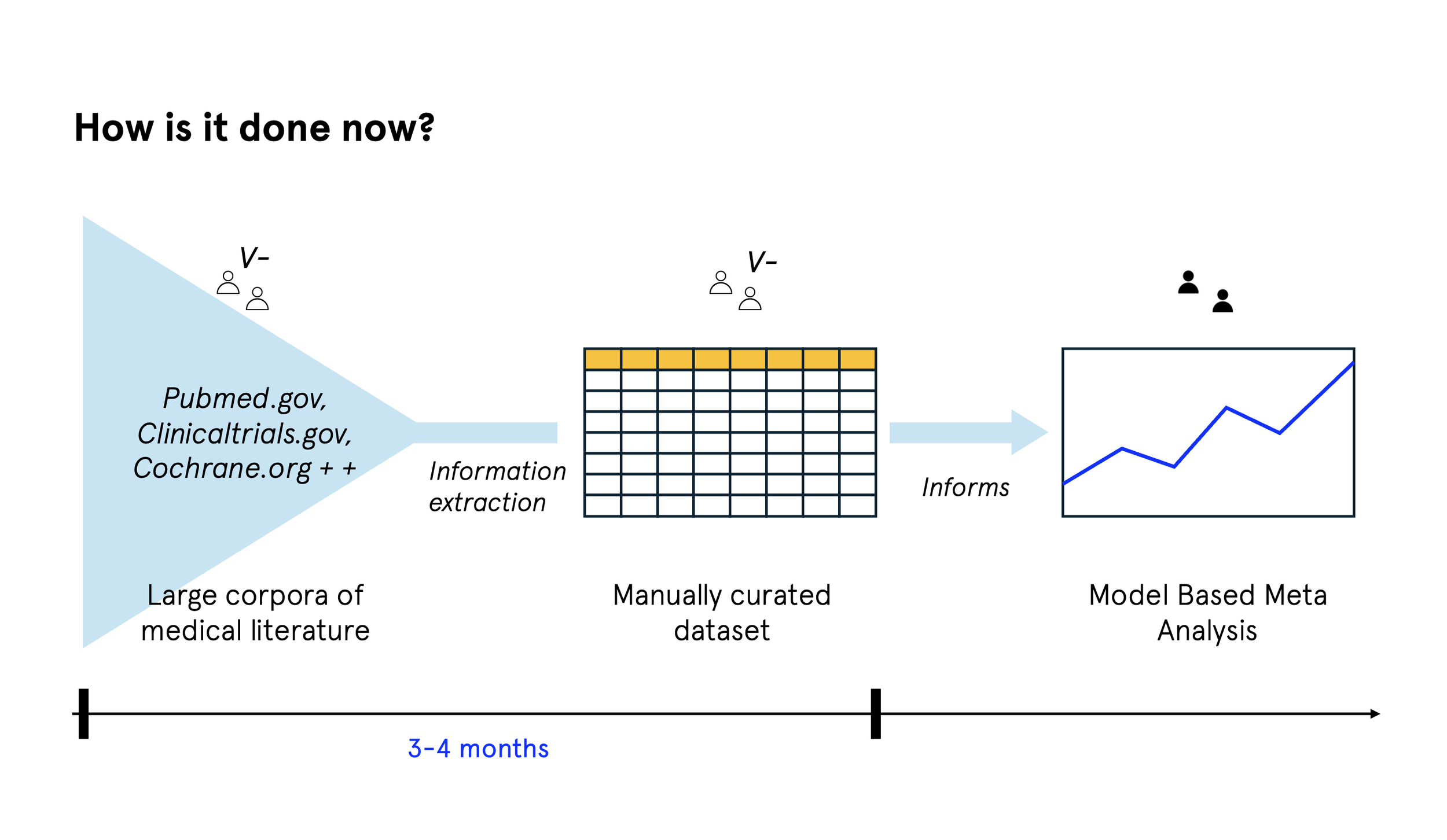

How manual curation works today

Model based meta analysis brings together data from multiple clinical trials to inform drug development decisions. In practice, this usually involves:

Finding relevant trials and publications

Manually extracting data from papers

Standardising that data into consistent formats

Assessing study quality and reliability

Running the statistical analysis

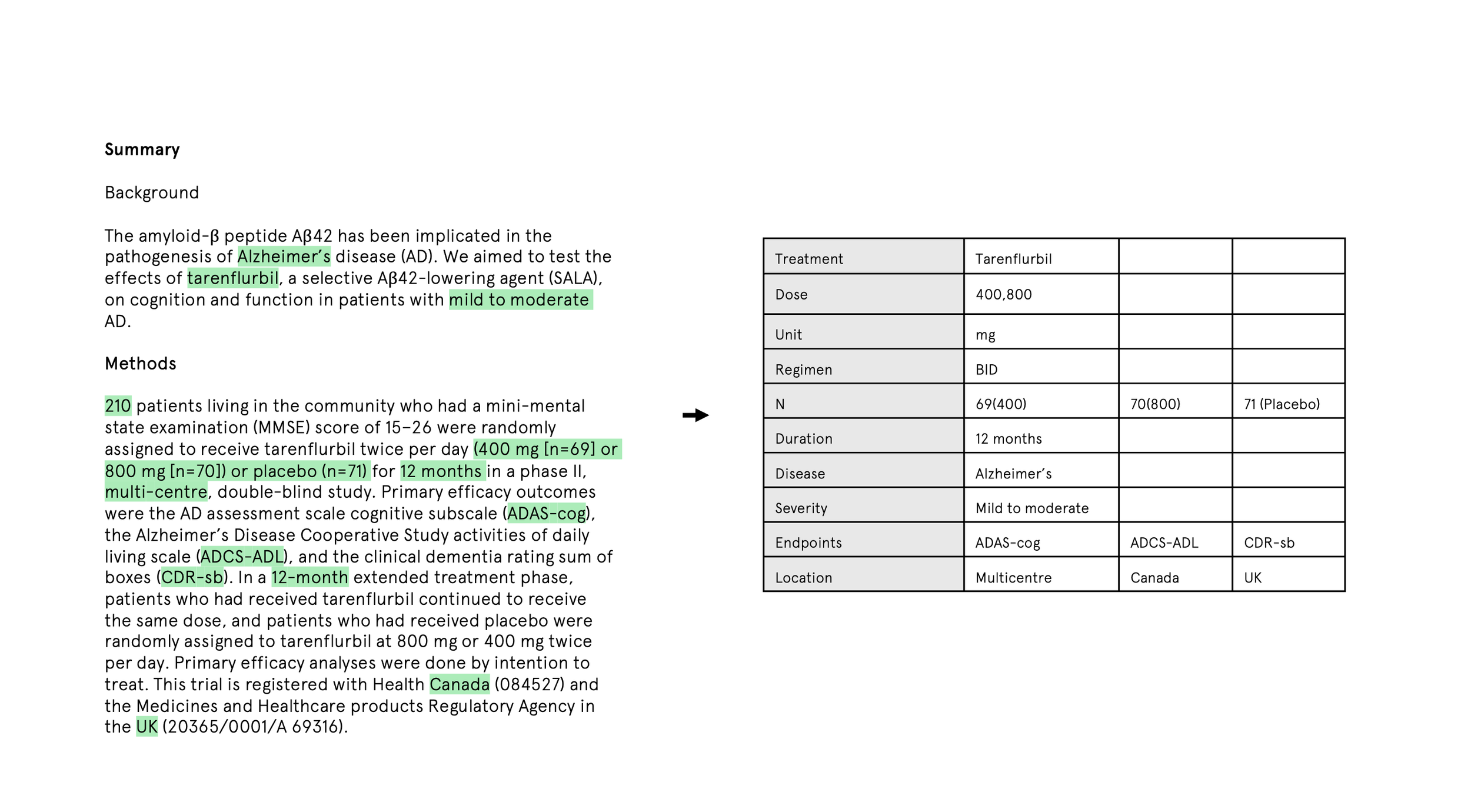

Most of the time is spent in the middle. Extracting and standardising data, and checking its quality, is slow, detailed work. A single meta analysis might involve 20 to 50 papers, with each one taking several hours to process. It requires deep expertise, but the work itself follows fairly consistent patterns.

In theory, LLMs can automate much of this. In practice, the prompt has to be very specific about what to extract and how to structure it. A pharmacokinetic analysis, for example, might need to spell out:

Which drugs and formulations matter

Which PK parameters to extract

Which patient populations to include

How dosing is defined

Which units to use and how to convert them

What to exclude on quality grounds

That means asking researchers to externalise their entire mental model of the analysis upfront. For most people, that is the real barrier.

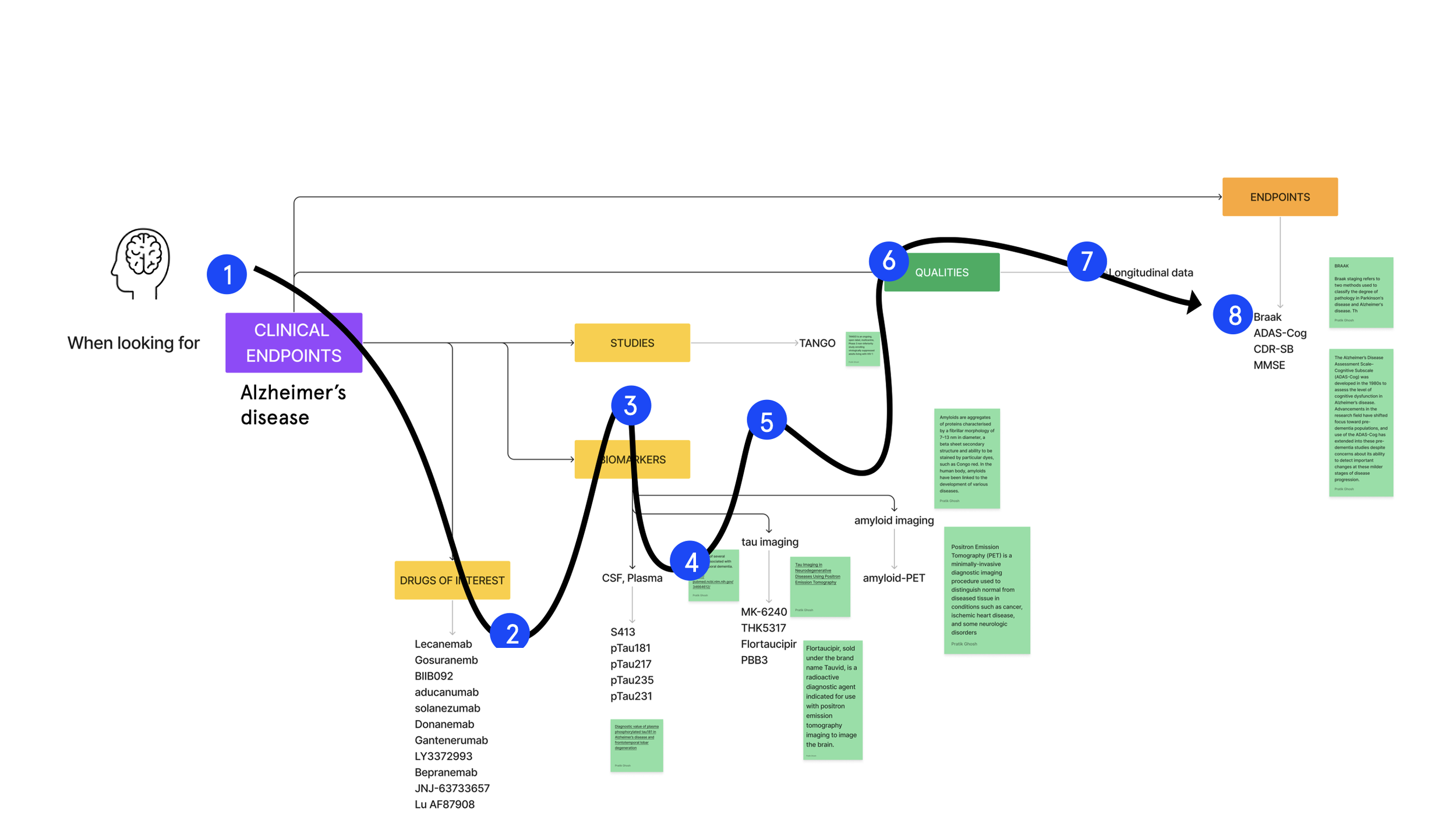

Task decomposition as an interface pattern

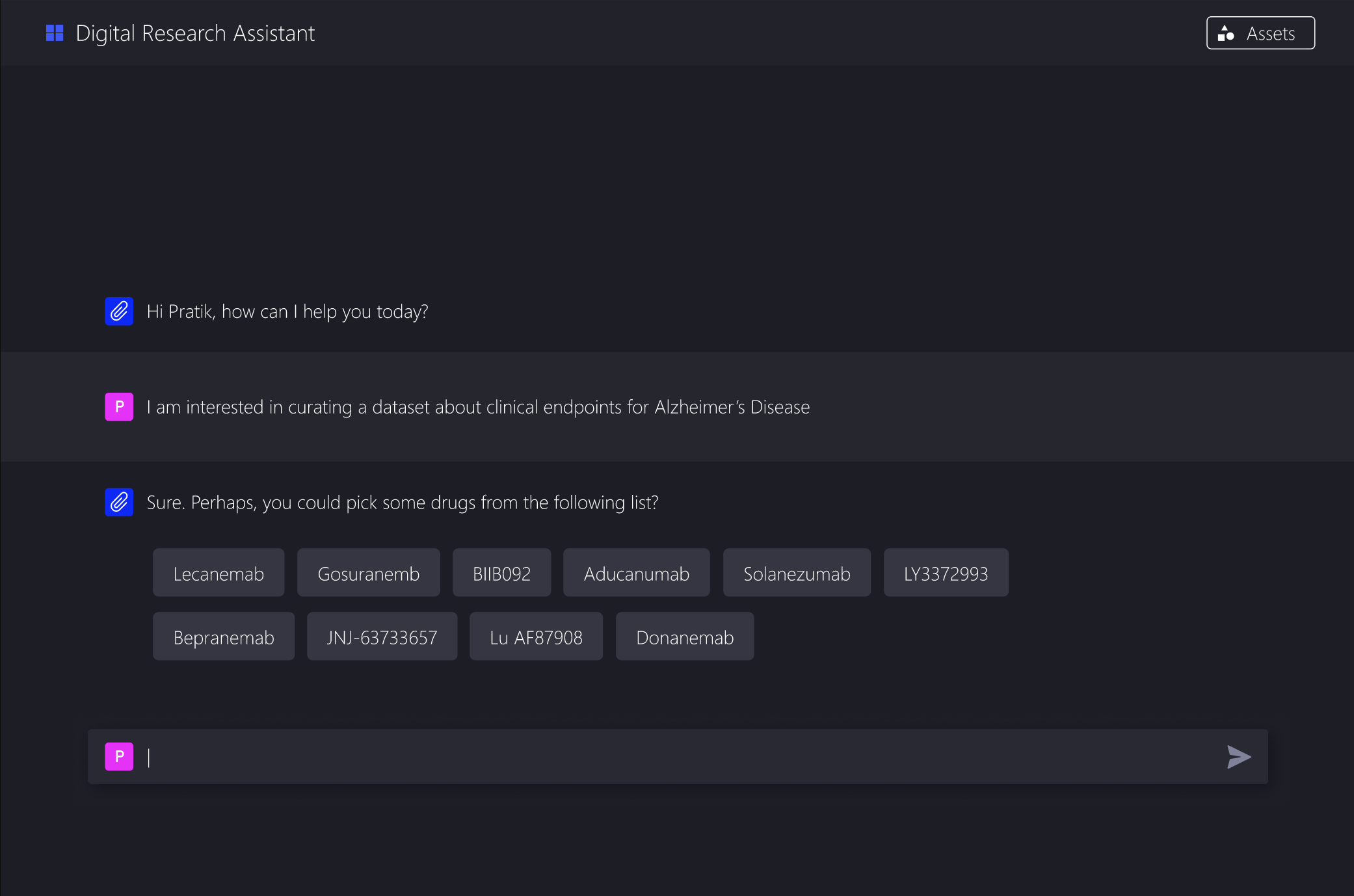

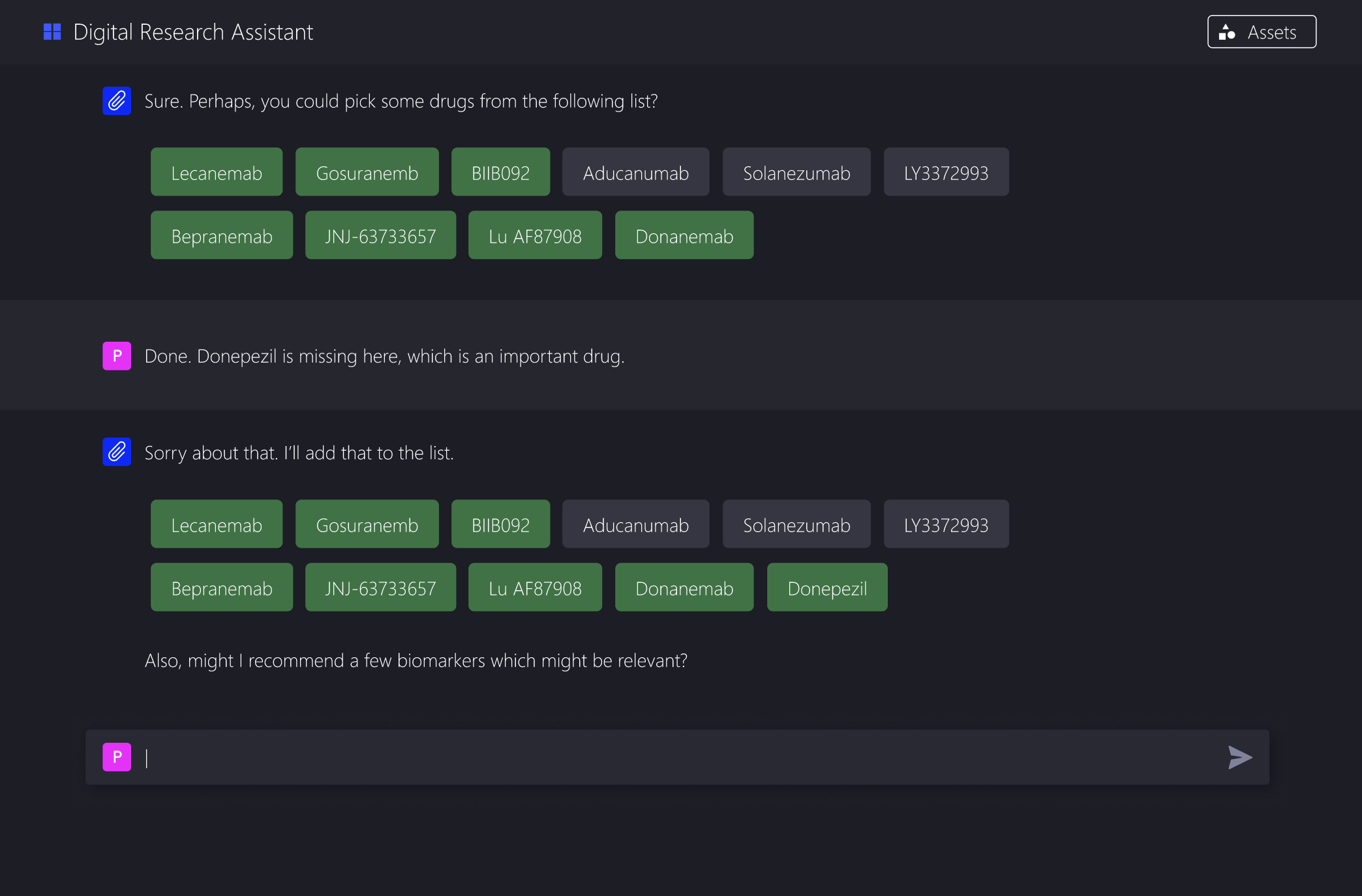

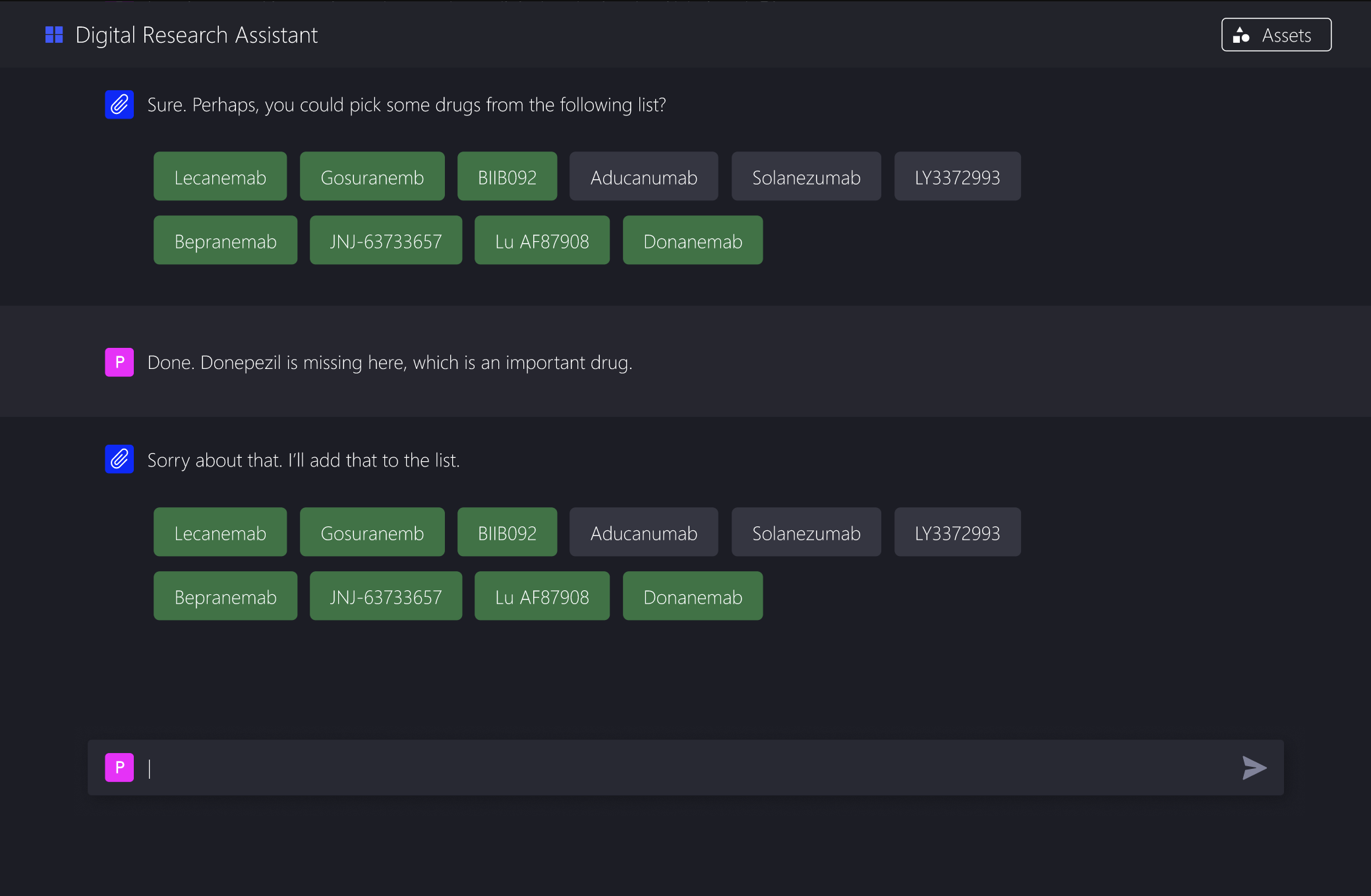

Rather than treating prompting as a writing task, we reframed it as a guided decision making process.

The system does not ask for a full prompt. It asks a sequence of questions, gradually building one in the background:

Start with high level questions about the analysis goal

Use those answers to ask more specific follow ups

Offer clear, clickable options grounded in domain knowledge

Show how each choice narrows the extraction criteria

Allow users to go back and refine decisions

Assemble the final prompt behind the scenes

This aligns much better with how clinical researchers already think. They are good at making informed choices when presented with concrete options.

Structuring the question flow

The questions are organised to mirror the logic of a meta analysis.

Level 1: Analysis type

What kind of analysis are you running?

Efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, dose response.

Level 2: Therapeutic area

Oncology, cardiovascular, immunology, and so on.

Level 3: Parameters

Based on earlier choices, the system presents relevant options. Endpoints for efficacy, PK parameters for pharmacokinetics, or adverse event categories for safety.

Level 4: Inclusion criteria

Patient characteristics, study design constraints, and data quality thresholds.

Each answer tightens the scope and adds detail to the underlying prompt.

Generating useful options

The system does not hardcode every possibility. Instead, it draws on a knowledge base to surface relevant choices:

Fixed options for stable categories such as therapeutic areas

Dynamic options drawn from drug databases, ontologies, and past analyses

This keeps the interface manageable while still covering a wide range of real world cases.

Building the prompt progressively

Every user selection maps to a prompt fragment. For example:

User choices might include:

Analysis type: Pharmacokinetics

Therapeutic area: Oncology

Drug: Compound X

Parameters: Cmax, AUC, clearance

Population: Advanced solid tumours

Behind the scenes, these are assembled into a structured extraction instruction. As the researcher moves through the questions, the prompt becomes more specific, more complete, and easier for the model to act on.

Templates exist for different analysis types, but they are modular. Components are combined based on the researcher’s decisions, rather than forcing everything into a rigid format.

Making the system legible

A core design principle was transparency. Researchers should be able to see what they are building and understand how their choices are interpreted.

The interface includes:

A live preview of the constructed prompt

A plain language summary of the extraction criteria

Clear points where users can jump back and edit decisions

This helps researchers trust the system and, over time, develop intuition for what makes an effective prompt without ever having to write one themselves.

Designing for how people think

The question flow deliberately moves from abstract to concrete based on the mental models of manual curation. Early questions are conceptual, such as the research question or analysis goal. Middle questions are categorical, such as which outcomes or parameters matter. Later questions deal with specifics like units, thresholds, and exclusions.

This avoids the blank page problem and reduces cognitive load. Each decision is simple on its own, but together they produce a sophisticated specification.

Interaction patterns

Single choice questions for mutually exclusive decisions

Multiple choice where criteria can be combined

Conditional questions that only appear when relevant

Progressive disclosure to avoid overwhelming users

The aim is cognitive ease, not speed for its own sake.

Practical challenges

Building this kind of system raises real technical issues.

The knowledge base has to handle drug name variants, parameter synonyms, unit conversions, and study design taxonomy. We addressed this with a structured knowledge graph that researchers can extend as gaps appear.

Some combinations of choices are invalid. For example, certain PK parameters do not make sense for particular dosing routes. Validation rules catch these cases early and warn users before time is wasted.

Different analyses need different prompt structures. Instead of fixed templates, we used modular components that can be recombined as needed.

What success looks like

This approach delivered clear benefits:

Researchers can create usable prompts in minutes rather than tens of minutes

Guided choices reduce common errors and omissions

People without prompt engineering experience can still use LLMs effectively

Prompts are often more thorough because the system asks for details people might otherwise forget

Most importantly, the interface removes the gap between expertise and automation. Researchers focus on their domain knowledge, not on how to talk to a model.

Meeting users where they are

The broader lesson is simple. Powerful tools fail when their interfaces demand skills users do not have.

Domain experts hold rich, tacit knowledge. They can make good decisions when presented with clear options. They prefer step by step processes and want to understand how systems interpret their input.

Task decomposition is not just a prompting trick. It is a general pattern for making complex AI systems usable. Break the problem down, ask questions people can answer, and assemble the complexity behind the scenes.

Implications for AI tools

This points to a shift in how we design LLM interfaces.

Not “here is a powerful model, learn to prompt it”, but “here is your workflow, the model adapts to how you think”.

As models improve, interface design becomes the bottleneck. The most effective AI tools will not be defined by their underlying models, but by how well they meet users where they are and help them think clearly about their work.